Note 16:

Peculiarity

Note 16a: Voiceless vowels

The

fado louco ©

sample shows how vowels (mostly

/i/,

/u/ and

/1/,

all close vowels, coincidence or not) in final

and initial position and also between voiceless consonants, can easily become very

short and voiceless in Portuguese.

More examples of this can be heard at the

Portuguese section

of the sound samples of the

Handbook of the International Phonetic Association:

In the narrative about the ‘sun and the northern wind’

(o sol e o vento norte)

in this material is the passage "até que o vento norte desistiu".

The syllables ‘tedesist’ are completely voiceless there, vowels

included: [nOrt1_O_Xd_O1_O_Xz_Oi_O_XStiw] or even [nOrttsStiw].

(In IPA phonetic transcription, such devoicing is indicated with a ring

below, symbol 0325, e.g. [u̥], here I used

X-SAMPA’s

_O for that.)

This devoicing of vowels is one of

the things that can make the spoken language so hard to understand to the

uninitiated foreign learner. Most other languages handle such cases

differently, so foreigners tend to misinterpret the situation, and fail

to recognise any words.

One other example is the word ‘intérprete’, which I heard

in Portugal on the

classical music radio

station called Antena 2.

This word has two normal voiced syllables (of course with the exception

of the t), but the third and fourth unstressed syllables (prete) are

completely unvoiced.

The same thing happens in the words mérite, polémico, príncipe,

eléctrico, trânsito (all of these have only one syllable),

Atlântico, fantástico, catástrofe, estereótipo,

o helicóptero (two syllables):

the syllable that bears the stress is voiced, but the two that

follow are voiceless, including the vowels.

Note 16b: Consonants clusters

I think we can take this reasoning a step further. It is often said that Portuguese people swallow most or all vowels, but I don’t think this is true: although short and sometimes voiceless, all the vowels are actually there.

I think what really happens – and what makes the language sometimes resemble Georgian or Tamazight, and Salishan languages, which are famous for their unlikely consonant clusters – is that the unstressed (and non-nasalised) vowels /i/, /u/ and /1/ do not make their own syllables. As a result, many words and expressions in which the uninitiated listener would expect many different syllables, in fact have far fewer, or even just one. Brazilian Portuguese does not have this feature, which is why Brazilians often find Spanish easier to understand than their own language as spoken by Portuguese or African people. They have almost as much understanding difficulty as other people, who have a completely different language as their mother tongue, because of this unusual way of building syllables.

Examples:

| Word or expression | Number of syllables (core vowel in bold) |

Max. number of adjacent consonants (not counting non-syllabic vowels) |

|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 1 (not 3) | 4 [prtg] |

| Português | 1 (not 3) | 4 [prtg] |

| telefonou | 1 (not 4) | 4 [tlfn] |

| telefonar | 1 (not 4) | 4 [tlfn] |

| o telefone | 1 (not 5) | 3 [tlf] |

| enigmático | 1 (not 5) | 3 [ngm] |

| helicóptero | 1 (not 5) | 3 [ptr] |

| Fevereiro | 1 (not 4) | 3 [fvr] |

| turístico | 1 (not 4) | 3 [stk] |

| de repente | 1 (not 4) | 3 [dR\p] |

| a ferro quente, malhar de repente | 6 (not 11) | 4 [rdR\p] |

| misterioso | 1 (not 5) | 5 [mstrj] |

| o descobridor | 1 (not 5) | 6 [dSkbrd] |

| os barcos dos descobridores | 2 (not 9) | 11 [rkSdSdSkbrd] (but in Portuguese this is about phones, not just written letters!) |

| refrigerante | 1 (not 5) | 5 [R\frZr] |

| frigorífigo | 1 (not 5) | 4 [frgr] |

| frigorífero | 1 (not 5) | 4 [frgr] |

| credulidade

(easily believing, from crédulo) | 1 (not 5) | 5 [krdld] |

| credibilidade

(easy to believe, from crível) | 1 (not 6) | 6 [krdbld] |

| meteorológico | 1 (not 7) | 4 [mtrlOZk] [m1tjwrwlOZjkw], this one attested on Rádio Graciosa, 26 June 2014 |

| metropolitano | 1 (not 6) | 6 |

| metropolitano de Lisbo a | 3 (not 10) | 6 |

| metropolitano do Porto | 2 (not 9) | 6 |

| estabelecimento | 2 (not 7) | 4 |

| o Terreiro do Paço | 2 (not 7) | 3 |

| o Terreiro do Paço que se .. | 2 (not 9) | 3 |

| terrorismo | 1 (not 4) | 3 |

| abuso de poder | 3 (not 6) | 4 |

| o primeiro-ministro | 2 (not 7) | 3 |

| o primeiro-ministro português | 3 (not 10) | 7 [Strprtg] |

| José Petronilho | 2 (not 6) | 4 |

| José Rodrigues dos Santos | 3 (not 8) | 5 [gSdSs] |

| São Tomé e Príncipe | 3 (not 7) | 2 |

| Centro Cultural de Belém | 3 (not 8) | 6 |

| este ditado novíssimo | 3 (not 9) | 4 |

| Diário de Notícias | 3 (not 9) | 4 |

| que depois de se ter despedido | 3 (not 10) | 5 |

| Livro do desassossego | 3 (not 8) | 5 [vrddz] |

| pacto de estabilidade | 3 (not 8) | 5 |

| Rádio Globo Digital (sample 1, (sample 2). | 3 (not 8) | 4 |

| Polícia de Segurança Pública | 6 (not 12) | 5 |

This latter example is what the letters PSP mean. If "segurança" could be replaced with a masculine word, so that "pública" would be "público", there would even be one less syllable.

One more example of my own hearing difficulties (even in 2004, after so much listening): in an old recording of a small-band internet tv newscast, I kept hearing something like comboios e autobus cidade. It didn’t make sense. Then suddenly, when hearing the expression in some other part of the recording, I realised what it really was: comboios de alta velocidade. The sonoric difference is much smaller than the spelling suggests. This was although I knew all the time that the subject was TGV lines to be built!

About "Pacto de Estabilidade" (the EU rule that the budget deficit may not

exceed 3 percent of the gross domestic product):

/paktud1St3bilidad1/ becomes [paktd_OSt3blDad_O], that is, the d of "de" becomes voiceless

being between [t] and [S], so it’s almost a [t] itself. The difference between the

two adjacent t’s is that the first one is u-coloured, labialised ([tw]), and

the second is not.

Terrorismo: Because the e and the o in the beginning of the words are short, weak and voiceless, here we see the two kinds of r in the same word, and in the same syllable: [tR\riZmw].

A sequence of four t’s!: "Liberte-te de teus problemas":

/libErt1t1d1teuSprublem3S/,

[libErttd_OteuSprublem3S] or even

[libErtttteuSprublem3S].

Rádio Globo

Digital

is a radio

station.

Director and presenter Diogo Pimentel pronounces the name himself in these fragments.

It’s fascinating to listen to for a non-native speaker like me. I know what happens,

why it happens, I can describe and explain it, but every time I hear it, it has already

happened before I know it, and I am amazed every time again.

Two more examples of extreme compression of utterances, from the film "Capitães de Abril":

- Maia! .... – O que é isto? [wkjEjStw] ©

- Olha que menina tão bonita. Como é que te chamas? © – Amélia. – Ah, que bonito nome!

Here’s one by fadista Ana Laíns on

Portuguese television, when she pronounces the title of the

song she’s about to sing. She says:

"Agora vai ser «O fado que me traga»" [wfaDwkmtrag3].

The presentator mirrors the expression and says:

"O fado que te traga" [wfaDwkttrag3].

Both times there are 3 syllables instead of 7, with a maximum

of 5 consecutive consonants.

Watch and hear the conversation and the lovely song

on Youtube.

Yet another fado related example: Maria Ana Bobone announcing the song she is going to sing, ‘Senhora do monte’. She says: “De Frederico de Brito, Senhora do monte”. The name of that famous poet and composer, including the preposition before it, has 2 syllables instead of 8, with a maximum of 4 consecutive consonants: [fr1D1rikwDbritw].

Note 16c: Vowel runs

A language with so many consonants and so few vowels could not be beautiful anymore, and Portuguese is. Perhaps in an attempt to keep the balance, it also developed long sequences of vowels and diphthongs. There are triphthongs, tetraphthongs, pentaphthongs, hexaphthongs, heptaphthongs, and even octophthongs.

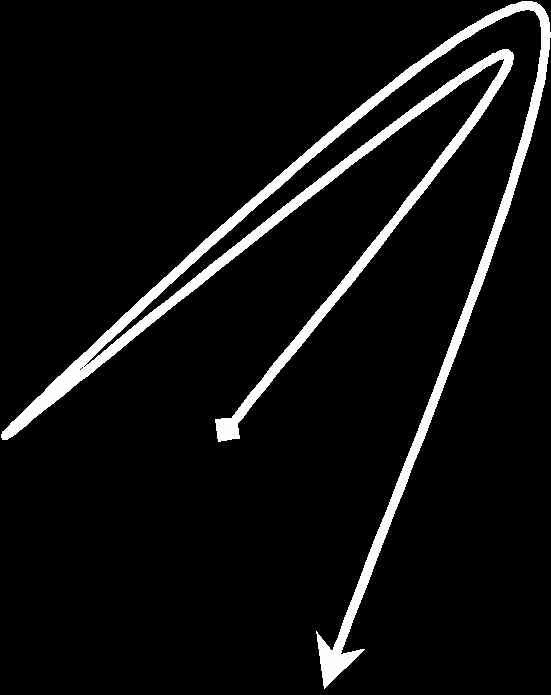

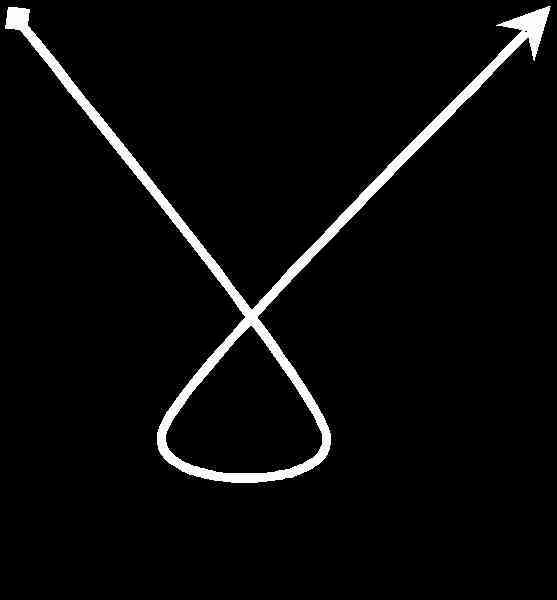

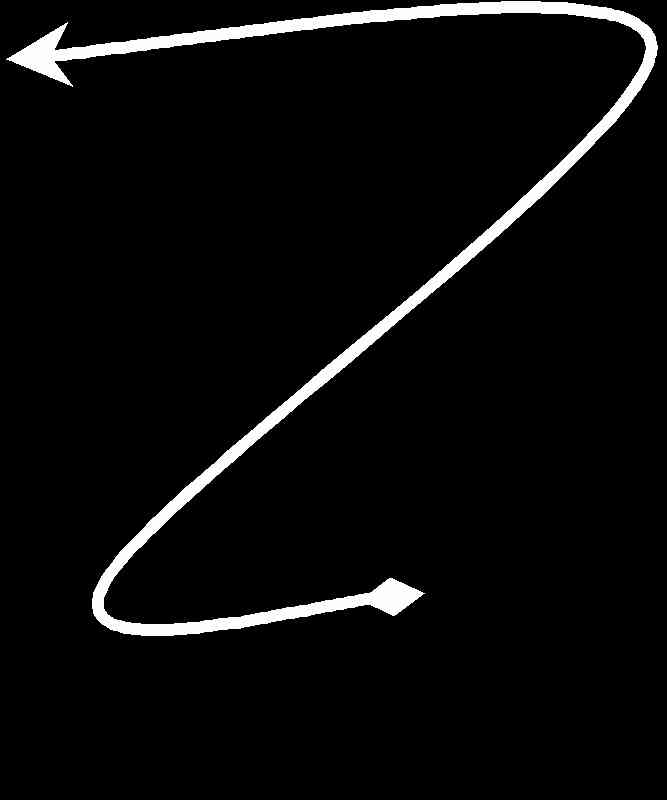

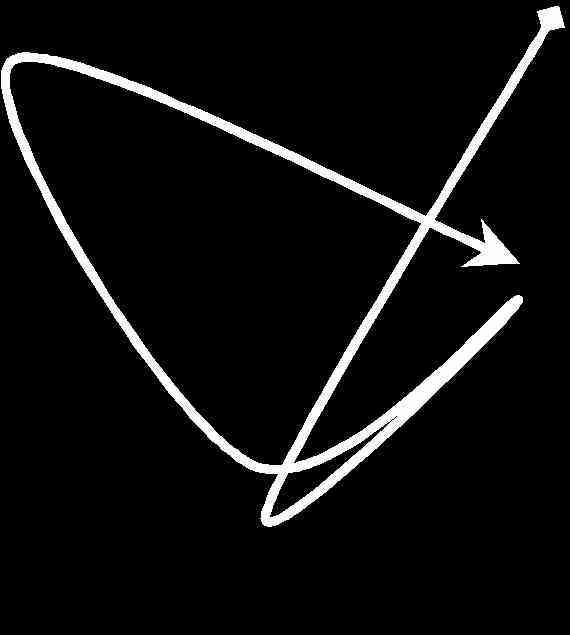

These combinations require complicated tongue movements, that aren’t easy to master for the non-native speaker. The diagrams show the position change of the top part of the tongue.

Some examples:

|

Meu coração é um almirante louco

/meukur3s3~u~Eu~almir3~t1loku/ (from "Ah, um soneto..." by Álvaro de Campos (Fernando Pessoa)) |

|

|

O teu dia

é o passado

/u teudi3Eup3sadu/ (from the poem Saudade by Luís Eusébio) |

|

|

A música é o elemento que une aquele ambiente

de vivências muito particulares.

/3muzik3Euil1me~tu/ (From an interview with fado singer Camané) |

|

|

A guerra contra o regime de Saddam Hussein foi há um ano

/foiau~3nu/ (Jornal 2, 18 March 2004, RTP) |

|

|

na água ou em outros líquidos

/agu3o3~i~otruZ/ (with a Lisbon or Coimbra accent) |

|

|

na água ou em outros líquidos

/agu3Oue~OutruZ/ (with a northern Portuguese accent) |

|

|

que têm ou há um ano tiveram

/t3~i~3~i~oau~3nutivEr3~u~/ An octophthong! (I hope this one is grammatically correct, because it is unattested, I made it up myself) |

|

|

Há um ano, ou há um ano e meio

This one doesn’t count, because of the n in ano and the m in meio, which are consonants. But, ignoring the comma (= pause), and considering that nasals, like vowels, are made with an uninterrupted air-stream, this is a uniquely long (17!) sequence of all-voiced free-flow speech sounds, where only timbre makes the difference. Perhaps languages like Hawai’ian can compete? Addition 15 February 2013: look at this! |

|

|

É o a ou o b?

This is a real attested one, heard on Rádio Felgueiras, said by presenter Flávio Gil on 22 June 2010, in a multiple choice quiz. "Is it (is your answer) a or b?" |

|

Note 16d: The essiness of the Portuguese language

I think part of the beauty of the Portuguese language lies in its

"essiness" (Dutch: "essigheid"):

this is the term I coined for its having so many

[s],

[z],

[S] and

[Z]

sounds, which also occur very close to each other

in at times bizarre succession. This is strengthened by the often very short

and sometimes

voiceless vowels.

It also makes the language more difficult to pronounce for me, being a native

speaker of Dutch. My language does have

[s] and [S]

too, but [S] is not very

frequent, and it may even be a combinatory variant of [s] when followed by [j],

instead of a separate phoneme. So assimilations, which in Portuguese do not

occur between these sounds, are difficult to avoid for me, unless I practice

examples many times.

Examples:

Pois se te ouço chorar eu também choro ©

[poiSs1tiousuSurareut3~b3~i~SOru].Homens e faces e os seus gestos como escritas ©

[Om3~i~zifas1ziuSseuSZeStuSkomuSkrit3S]Todos esses esforços © [toduzes1z1SfOrsuS] or [toduzesSfOrsuS] (all these efforts). See also note 20, word-initial es.

26 June, 2008: "A TAP anunciou um plano de emergência. Nos primeiros cinco meses do ano, a companhia registou um prejuízo de cento e dois milhões de euros. Esta reviravolta nos resultados é explicado pela empresa com a escalada dos combustíveis. A TAP diz que todos os esforços são necessários © para peser ..., preservar a companhia."

/toduzuz1SforsuSs3~u~n1s1sarjuS/

[todwzwzSforswSs3~u~s:arjuS]What makes this so hard to understand for the uninitiated foreign learner, is this:

In the word "necessários", the vowels after the n and the c are very short and voiceless. They tend to be elided, so the two sounds [s] merge into one. See also cessar fogo below.

The n of the same word "drowns" in the preceding nasalised diphthong. This is because normally, the transition between having an open nose channel for the nasalised vowel, and having it closed for the following consonant, may happen slightly later than the start of the consonant. That means the transition may resemble [n] (if the closure is full, e.g. in preparation of a plosive sound). As a result, in this case the n may completely vanish.

So the actual pronunciation of "são necessários" may be close to "são sários"!

Ciências sociais © [sie~si3SsusiaiS] (social sciences).

Consciênte /ko~Ssje~t1/, consciência /ko~Ssje~sj3/.

Tu que nasces, e renasces ©, when read slowly [tuk1naSs1S iR\1naSs1S], but without the comma and very fast, with elided non-syllable-forming vowels: [tuknaSszR\naSsS].

Este sistema [eSt1siStema], or in reduced form [eStsStema], esse sistema [es1siStema] or [essStema].

Pudesse-te eu amar sem que existisses /kiziStis1S/, or with non syllabalizing vowels out: [kzstisS] (only 1 syllable) (Fernando Pessoa).

Estilhaçar /StiL3sar/ (to splinter): not very essy, but difficult for me because the palatal lh tends to interfere with the non-palatal ç. The second person past subjunctive is much essier: estilhaçasses /StiL3sas1S/ [StL3sasS] (only 2 syllables).

Exigências /iziZe~sj3S/ [zZe~sj3S] (necessity, requirement).

Dirige-se já! /diriZ1s1Za/ [driZsZa] (From a radio commercial: "contact us now!").

Preços baixos sempre /presuSbajSuSse~pr1/ [presSBajSSse~pr] (Supermarket slogan).

Cessar-fogo /s1sarfogu/ [ssarfogw] (cease-fire). It took me a long time to find this word in a dictionary. It is not listed under sarfogo. The word pustinhanos, sometimes used in the same context, is also hard to find. Look it up under words beginning with pale.

In the word "sucessivamente" we see three s’s in quick succession: [sssv3me~t], or with consonant colouring: [sws1sjv3me~t1].

A disciplina do ritmo é aprendida até ficar sendo uma parte da alma: o verso que a emoção produz nasce já subordinada a essa disciplina.

[prwduZnaSsZaswb]

(Fernando Pessoa sobre o seu heterónimo Álvaro de Campos).Heard on Rádio Amália on 17 March 2015 and many times before:

"com as suas sugestões", [ko~3Ssu3SswZ1sto~jS].

Copyright © 2000-2007 by R. Harmsen